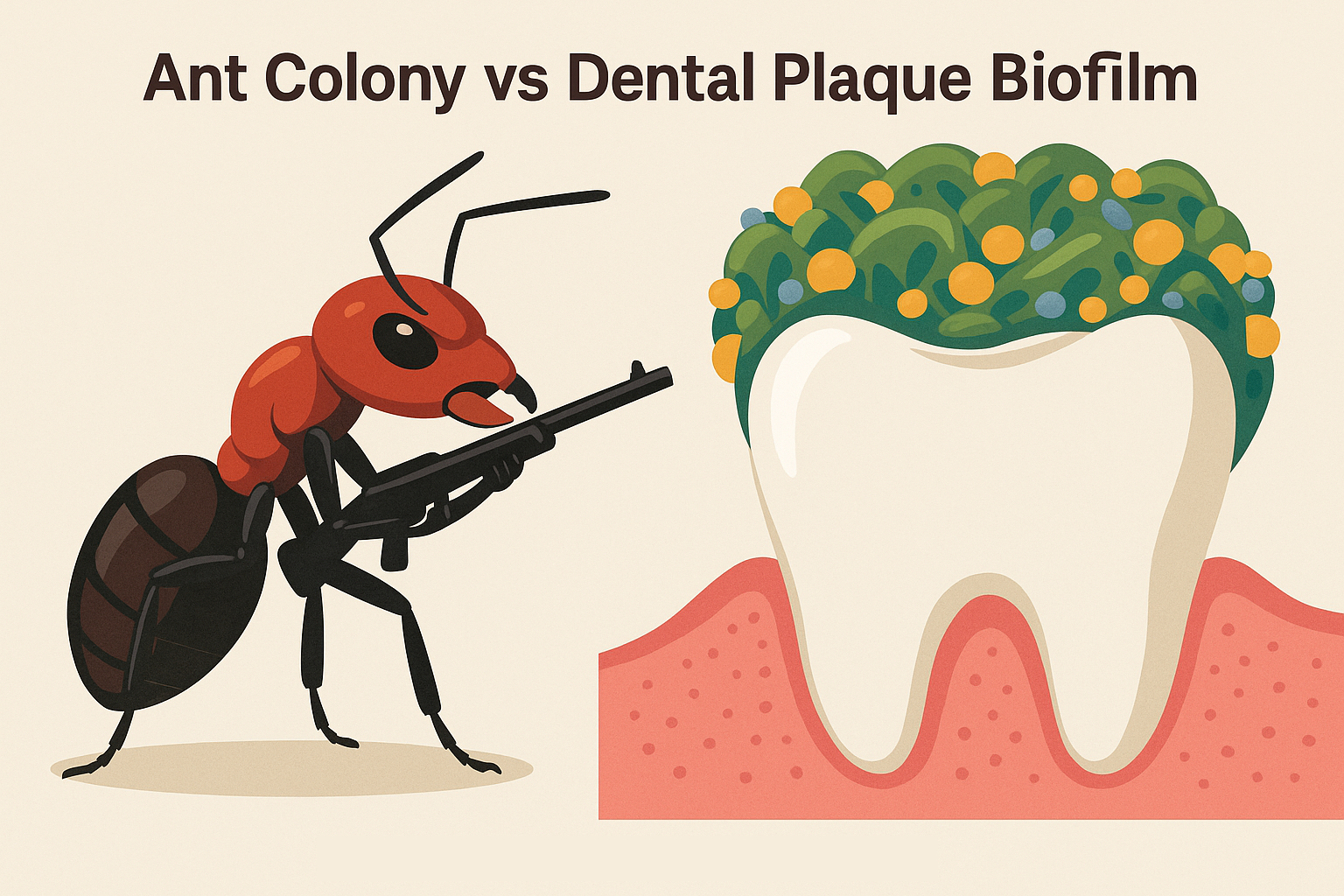

A swarm of ants can clean an animal carcass down to bare bone with astonishing speed.

Not because any single ant is powerful, but because thousands, even millions, act together — each equipped with razor-like jaws designed for cutting and tearing. In dentistry, there’s a similar lesson hiding in plain sight: microscopic bacteria, weak on their own, become a formidable force when they organize into a dental plaque biofilm. If that colony isn’t disrupted daily, it quietly breaks down enamel, inflames gums, and reshapes your oral health.

Ant colonies: why “small” doesn’t mean “weak”

When people imagine power, they picture lions, not ants. Yet ants dominate by numbers and coordination. Each individual has a simple job, but together they move mountains of sand, defend territory, and—under the right conditions—reduce a carcass to bone. Their advantage isn’t brute strength; it’s organization, persistence, and sheer headcount.

That same playbook appears in human biology. The tiniest actors can have outsized effects when they cooperate. In your mouth, bacteria form layered communities with division of labor, chemical signaling, and protective barriers. It’s not a stretch to say you host a bustling city on each tooth surface—better known as a dental plaque biofilm.

What is a dental plaque biofilm?

In everyday terms, plaque is not just “gunk.” It’s a living, structured community of microbes embedded in a sticky matrix they produce themselves. That matrix works like scaffolding and a shield. Within it, bacteria:

- Stick and stack: pioneer species attach to enamel; others latch on top, building layers.

- Communicate: they exchange chemical signals (quorum sensing) to coordinate growth and defense.

- Share resources: they pass along nutrients and even genetic material that can increase resilience.

- Resist attack: the matrix slows down antimicrobials and neutralizes some immune responses.

Left alone, this living film matures. Acids from bacterial metabolism start dissolving minerals from enamel, and toxins near the gumline provoke inflammation that can progress to periodontitis. This is why dentists emphasize disrupting the dental plaque biofilm every single day.

Ants vs. oral bacteria: the parallels that matter

1) Power in numbers. A single ant achieves little; a colony transforms landscapes. Similarly, a few stray bacteria pose little threat, but billions in a structured dental plaque biofilm can demineralize enamel and inflame gums efficiently.

2) Trail marks vs. chemical signals. Ants follow pheromone trails to coordinate swarms. Oral microbes rely on quorum sensing to switch behaviors together—turning on genes for adhesion, acid production, and matrix building when they reach critical density.

What is quorum sensing?

Quorum sensing is how bacteria “talk” to each other using chemical signals. Each bacterium releases signaling molecules (autoinducers). As more bacteria gather, these molecules accumulate. When the concentration passes a certain threshold, bacteria detect it and change behavior together. For example, they may start producing acids, forming biofilms, or activating genes that protect them — behaviors that make sense only when many bacteria act together.

Why it matters for dental plaque biofilm:

In dental plaque biofilm, quorum sensing helps bacteria organize, protect themselves, and become more resistant. That’s one reason regular brushing and flossing are needed to break down the biofilm before it becomes harder to remove or causes more damage.

3) Defensive fortresses. Ant colonies build protected nests; mature plaque creates a physical and chemical barrier that shelters bacteria from toothpaste ingredients, mouthrinses, and even immune cells. That’s why once a dental plaque biofilm matures, it’s harder to control.

4) Resource exploitation. Ants strip a carcass quickly because nutrients are concentrated and accessible. In the mouth, frequent sugar exposures provide fast fuel; bacteria metabolize sugars into acids that lower pH and accelerate enamel dissolution.

How a microbial “army” damages teeth and gums

Caries (cavities): mineral loss by acid attack

When acidogenic bacteria metabolize sugars, the pH dips. Below a critical threshold (around 5.5), enamel begins to lose minerals (calcium and phosphate). Repeated or prolonged low pH periods outpace natural remineralization from saliva, and a lesion forms. Early lesions can be arrested or reversed with lifestyle change and remineralizing support; more advanced lesions require restorative care. Left unchecked, a dental plaque biofilm is the main driver of this cycle.

Gingivitis and periodontitis: inflammation at the margins

At the gumline, a maturing film accumulates toxins and triggers the immune system. First, you see gingivitis—redness, swelling, bleeding on brushing. If the film persists, inflammation can progress below the gumline, where a more pathogenic community thrives. Tissue attachment loosens, pockets deepen, and bone resorption can follow—this is periodontitis. Like an ant colony undermining a structure, the microbial community changes the local environment to its advantage. The foundation of this process is the dental plaque biofilm.

Halitosis: volatile byproducts

Some oral microbes produce volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) that smell unpleasant. A thick tongue coating and neglected interdental areas are common sources. Mechanical disruption, especially of the posterior tongue, is often the most overlooked fix.

Why some mouths struggle more than others

- Frequency of fermentable carbs: snacking or sipping sugary drinks keeps pH low, favoring acid-producers.

- Saliva quantity and quality: saliva buffers acids and brings minerals; dryness (medications, mouth breathing) increases risk.

- Existing restorations and crowding: niches and roughness give the dental plaque biofilm more places to hide and mature.

- Systemic factors: diabetes, smoking, and chronic stress can tilt the balance toward inflammation and disease.

Stop the takeover: practical ways to disrupt the “colony”

1) Mechanical disruption: your daily reset button

- Brush at least twice daily with a soft brush for 2 minutes; angle bristles gently toward the gumline.

- Clean between teeth daily (floss, interdental brushes, or water flossers). Interproximal zones are the dental plaque biofilm’s favorite hideouts.

- Don’t forget the tongue: a quick scrape or gentle brush reduces odor-causing communities.

2) Chemistry that helps (without overdoing it)

- Remineralizing agents: support re-hardening of early lesions.

- Antimicrobial rinses: useful during high-risk periods or after treatment; rely on daily mechanical cleaning as the foundation against the dental plaque biofilm.

- pH-aware care: sugar-free gum with xylitol after meals can stimulate saliva and encourage a neutral pH.

3) Eating pattern > perfection

- Batch your sweets: enjoy them with meals instead of continuous grazing; fewer acid attacks, more recovery time.

- Protein, fiber, and micronutrients: support saliva and tissue repair. Vitamins D and C, calcium, and phosphates all contribute to resilience.

- Hydration: dryness concentrates acids and slows neutralization—sip water, especially if you mouth-breathe or take drying meds.

4) Professional disruption: reset the battlefield

A professional cleaning removes mature, calcified deposits that home care can’t touch. Think of it as dismantling a fortified outpost so your daily efforts can keep the terrain clear. Periodic exams also catch early enamel changes and gum inflammation before they escalate. This is especially important if the dental plaque biofilm has hardened into tartar.

“But I brush!” — why problems can persist anyway

Technique and coverage matter as much as frequency. Common gaps include hurried back molars, the tongue side of lower front teeth, and the gumline. Another pitfall is timing: if most of your sugar hits come in the evening and you snack until bed, you set up an overnight low-pH window when saliva flow drops, giving the film hours to consolidate.

From bone-stripping ants to smile-saving habits: the core lesson

Ants don’t “win” because they’re big—they win because they are many, organized, and relentless. Likewise, a mature dental plaque biofilm isn’t scary because each bacterium is fierce; it’s dangerous because the community protects, feeds, and amplifies itself. Disrupt the community frequently and kindly, and your mouth becomes a poor place for that army to thrive.

Action checklist (printable summary)

- Brush 2×/day, 2 minutes, with attention to the gumline and back molars.

- Clean between teeth daily (choose a method you’ll actually use).

- Scrape/brush the tongue—especially the back third.

- Cluster sweets with meals; minimize constant sipping of sugary/acidic drinks.

- Use remineralizing and antimicrobial tools strategically, not as a substitute for brushing.

- Schedule routine professional cleanings to reset difficult areas and keep the dental plaque biofilm under control.

Further reading & resources

NIH MedlinePlus — Dental plaque overview · American Dental Association — patient resources on plaque and gum disease

Explore more on ToothWiz: Weird Dental Facts · ToothWizVitamins: professional-grade wellness support

Takeaway: Ant colonies can strip bone because they work together. In your mouth, a dental plaque biofilm uses the same strategy—numbers, structure, and persistence.

Disrupt the colony gently every day, give your teeth time to recover between acid hits, and get periodic professional help to dismantle entrenched strongholds. Tiny armies only win when we ignore them.