Ethics in Dentistry: When “Right” and “Wrong” Aren’t Always the Same

The Complexity of Ethics in Dentistry

Dentistry is a field where science, skill, and compassion intersect. Our training emphasizes precision, best practices, and achieving the most durable result possible. But ethical dentistry isn’t always about doing everything that could be done.

Sometimes, the most ethical decision is to do less. Other times, it is to go further, even if the prognosis seems uncertain. In both situations, the heart of the matter is the same: aligning treatment with the patient’s values, goals, and quality of life.

Ethics in the Nursing Home Setting

One of the clearest examples is treatment in nursing homes. Many residents have multiple health conditions, limited mobility, and in some cases, a short life expectancy. For them, the “ideal” approach—comprehensive restorations, multiple appointments, or elective procedures—may not add value to their lives.

In these cases, focusing on comfort, infection control, and dignity often provides more benefit than pursuing textbook dentistry. The ethical question in ethics in dentistry is not, “What would be perfect treatment?” but rather, “What treatment will make this person’s life better right now?”

When Care Gives More Than Teeth Back

I once treated a patient in private practice who told me he wasn’t expected to live very long. Other dentists had declined to take him on, assuming it wasn’t worth the effort. He wanted to know what dental conditions he had and how they could be addressed.

I found areas of decay and other problems that could be treated. He chose to proceed. On a follow-up visit, he stopped to thank me. He explained that when he first walked into my office, he was filled with doom and gloom. But now, with those issues corrected, he felt better—not just physically, but emotionally.

The dentistry didn’t change his medical prognosis. What it did change was his outlook. The act of being cared for gave him dignity and optimism. In that sense, the treatment was profoundly ethical.

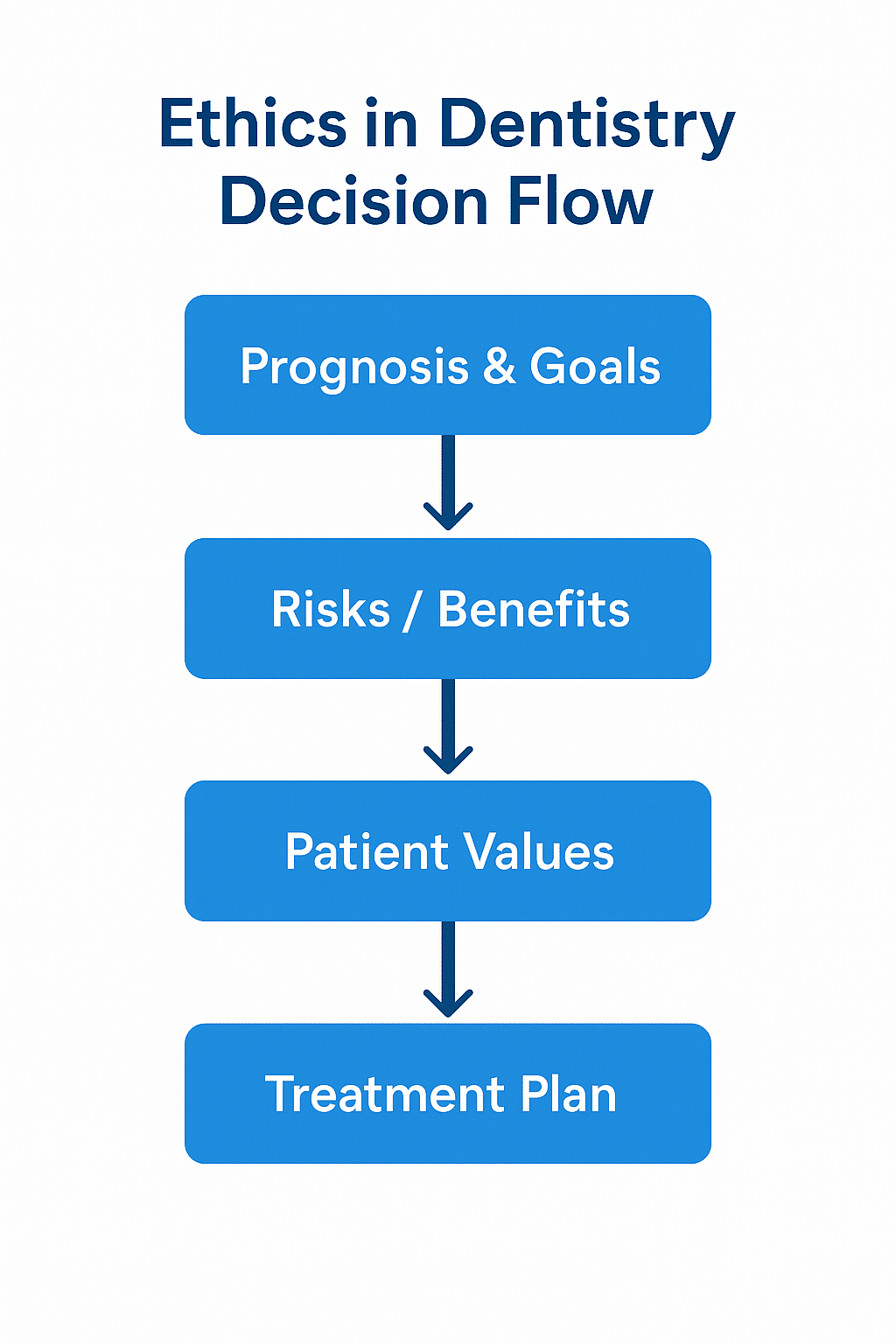

A simple framework for aligning treatment with prognosis, risks, and patient values.

The “Too Fragile” Patient Who Outlived Expectations

Another patient stands out in my memory. She had avoided treatment for years, insisting she had a weak heart and that dental work wasn’t worth the risk. Ten years later, she was still alive—having outlived her husband.

Her story is a reminder that prognoses are uncertain. While we must be mindful of risks, sometimes withholding treatment based on assumptions about longevity or fragility does patients a disservice. Ethical dentistry means weighing not just the clinical facts but also the possibility that a patient’s story may not unfold the way we expect.

Balancing Health, Ethics, and Economics

In modern healthcare, financial pressures are real—for both practices and patients. But ethics demands that we avoid letting economics drive decisions more than patient benefit. Dentistry that focuses solely on the bottom line risks neglecting the patient’s well-being, just as much as overtreatment risks exhausting their resources without real gain.

True ethical practice finds the balance: treatments that are practical, compassionate, and supportive of the patient’s life goals.

Guiding Principles for Ethical Dentistry

These principles reflect how ethics in dentistry can guide everyday decision-making:

Respect Patient Autonomy

Listen carefully to what patients value and want for themselves.

Avoid Overtreatment

Don’t recommend procedures that add burden without adding benefit.

Consider Quality of Life

Small improvements can make an enormous difference in comfort and confidence.

Stay Flexible

Ethics isn’t a rigid checklist—it adapts to circumstances.

Communicate Openly

Patients should be active participants in choosing the path forward.

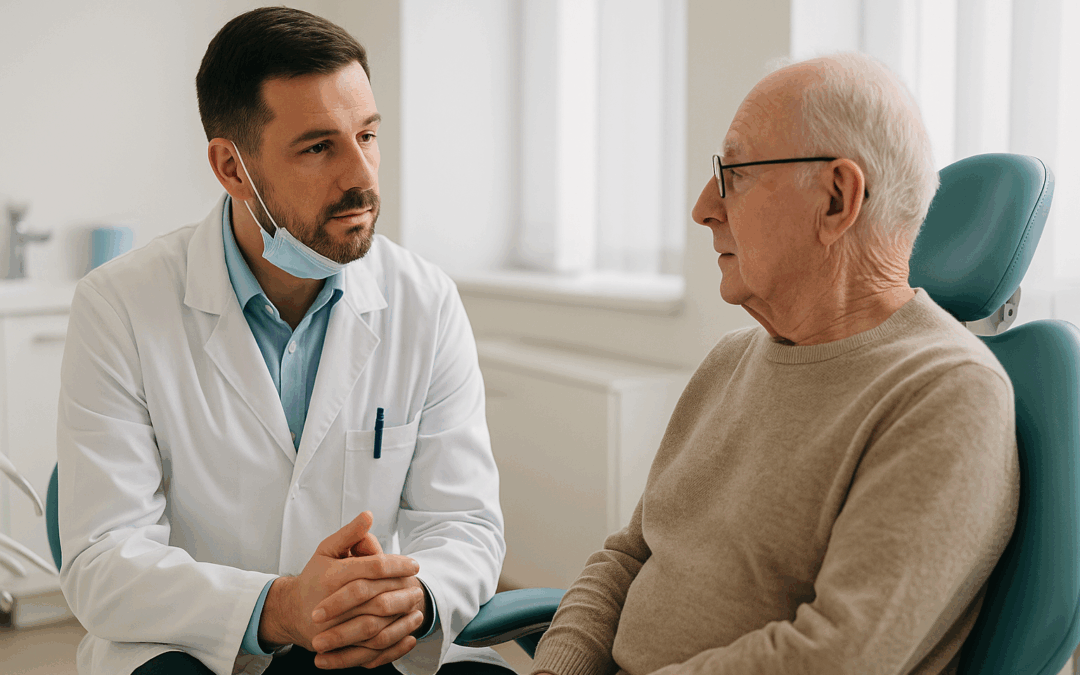

Balanced decision-making is central to ethics in dentistry.

Conclusion

Dentistry is not just about fixing teeth—it is about caring for people. Ethics in dentistry means recognizing that what is “right” isn’t always the same for every patient. Sometimes less is more. Sometimes more is necessary.

By staying patient-centered, balancing compassion with practicality, and resisting the pull of a one-size-fits-all approach, we honor the deeper purpose of our profession: helping people live with dignity, comfort, and optimism—no matter their circumstances.

Further Reading: